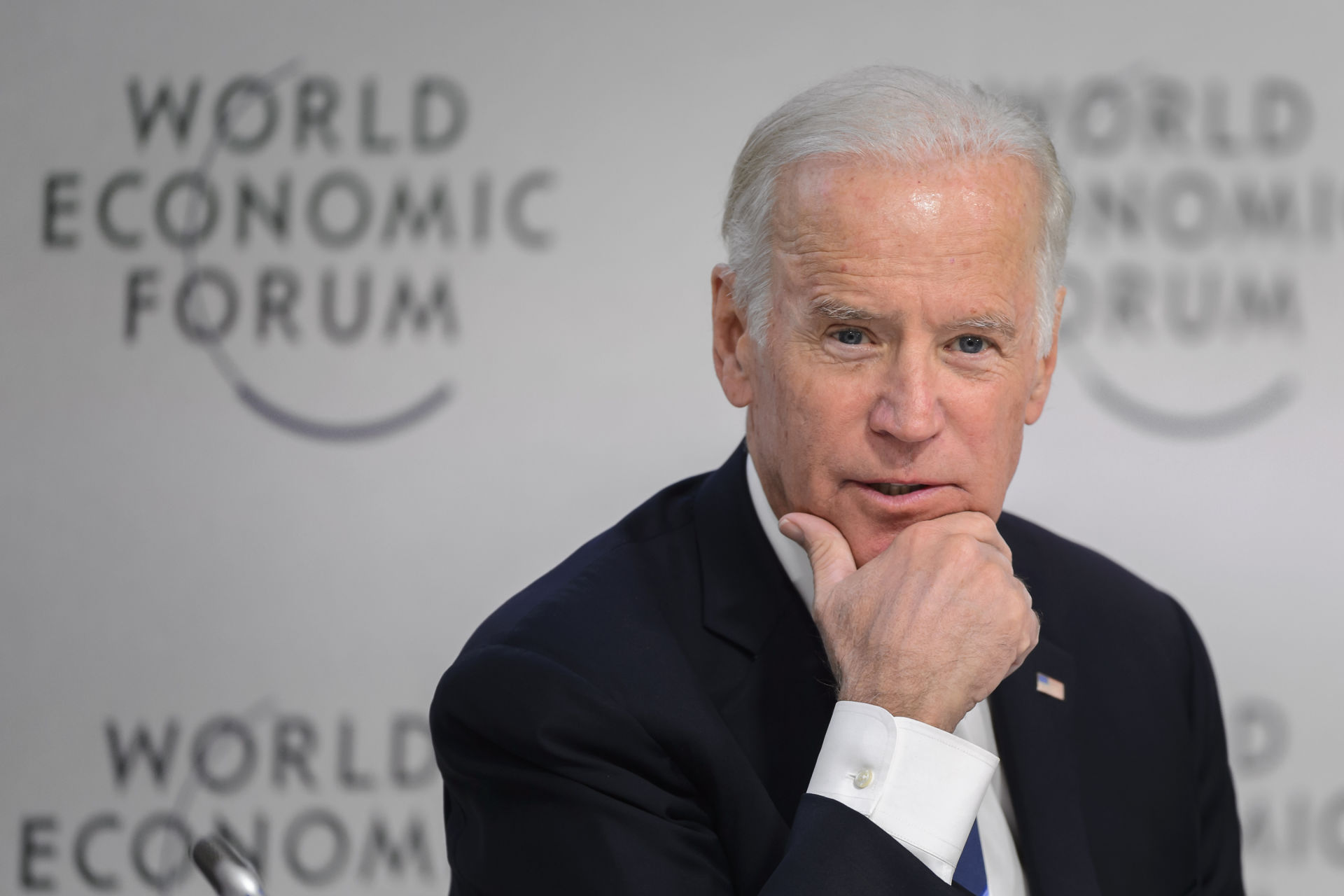

Joe Biden’s Push to Cure Cancer.

Joe Biden’s Push to Cure Cancer.

The cancer moon shot proposal that Joe Biden has been pushing for has been quite the controversy within the research community due to the fact that scientists have been pointing fingers at ingrained medical establishments for keeping data for themselves as opposed to using it to make much needed advancements to cancer treatments.

Beau, Joe Biden’s son, had died of brain cancer sometime in may. According to Biden, there are large amounts of data and research “trapped in silos, preventing faster progress and greater reach to patients.” Despite many scientists agreeing with this, most are still very hesitant in sharing any of the information and data that they use.

An editor of the New England Journal by the name of Jeffrey Drazen and co author Dan Longo had written that while contributing information is a good thing, it has to be done as a team, not by “data parasites” who may have embezzled years of work done by bench scientists.

“Big Data” has allowed for many advancements, however, it has also caused scientists to jump on the defensive. Even reports on the research papers that many build their careers out of have come down to saying that the results are ones that can’t be reproduced. The only way to get consistent results for many genetic studies is to share them and create a large sum of data. The problem with this is the fact that they lose the fame of publishing this data on their own.

Careers of researchers are built upon publishing their own research. On top of this, the medical institutions push to sell the data along with universities to advertise their discoveries under the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act.

Ethical review and data management committees jump in on the whole ordeal to defend patient’s rights and scientific integrity. This has a tendency to appear like a lost cause, creating red tape and silos that intimidate efforts of the administration.

Some kind of incentive may be required to cut them loose, said John Wilbanks of Sage Bionetworks, a nonprofit that supports open science projects.

“If they’re serious about a moon shot, they have to advocate for the creation of a new system that doesn’t have to fight all these various power structures,” says John Wilbanks of a nonprofit by the name Sage Bionetworks. Joe Biden has agreed to “break down silos and bring all the cancer fighters together”. Thing is, he has yet to provide any details as to how he plans to do this.

“Biden is absolutely right to focus on robust data sharing as a key tenet of cancer research,” says the chief medical officer of DNAnexus, David Shaywitz. “Leading academic cancer centers are clamoring for government money to subsidize sequencing projects, but unless this funding is explicitly coupled to actual data sharing, we’ll wind up enlarging existing silos rather than leveling them.”

“Data sharing is in the Zeitgeist—that’s why Biden said it” says Wilbanks. “But to force the transition to easier data handover, it will be necessary for the government to attach strings to its grants” he says.

Many researchers in the private sector disagree. “I don’t think that kind of mandate will work,” said vice president at the academic publisher Elsevier, Brad Fenwick. He said many of these concepts show “lack of appreciation of the difference between disciplines. Everyone sees the world from where they sit.” Many scientists “perceive very little upside in generously and richly sharing their raw data,” Shaywitz agrees. “At a minimum, it’s regarded as a thankless hassle.”

“At what point is data so free that you might wake up and find some part of your long, arduously created trial published by someone you’ve never heard of?” says chief advocacy officer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Clifford Hudis.

Donald Berry of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston mentions that there are also liabilities to open distribution of data. Unseen pieces of a dataset, such as details about that are not within the study but known only to the original researcher, can create errors when combined with other sets of data.

NIH funds clinical trials and normally needs the data to be published inside a year of when the trial was completed. Prematurely releasing the data before it’s collected can cause a bias. However, to reach the goal of an individualized approach to cancer, genetic differences of patient’s need to be compared to large databases of others with the same type of cancer. It’s simply impossible to do when gaining admittance to all that data can take several months, even more so when the patient is seriously ill with cancer.

“Everything we do in the rare disease space totally relies on data sharing,” says a genomics expert with appointments at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard by the name of Daniel MacArthur.

“’Research parasites’ is a rather hilarious thing to say,” adds Jeremy Leipzig. “A statistician sitting in India might have nothing to do with your study, but have an excellent way of analyzing data that gives us terrific insight into the etiology of a disease.”

The NIH’s Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes is a prime example of the issues with sharing. It was made in 2006 to catalog and issue out biomedical data generated in NIH funded studies. Often times it would take several months to find out if the scientists can even check the files, even ending up being denied without a reason given.

The government isn’t completely to blame though. Each establishment that gives away data to the site has individual guidelines that can differ from study to study. Exchanging vast files can be susceptible to technical difficulties. The staff at NIH don’t have enough funds compared to the work required to manage the database.

Regardless of all of the aforementioned reasons, less than one third are denied when trying to gain database access. Many that were interviewed for this article are noticing that data sharing is becoming more accepted.