A new immunotherapy study involving mice may have shown a new way to fight cancer. Scientists injected a bunch of dying cells, called necroptotic cells, into tumors. The presence of the dying cells sent a signal to the immune system to go to the tumors and attack all the cells there. This technique shrunk tumors in the mice. The researchers think this could be used in combination with immunotherapies to help fight cancer. The study was published in Science Immunology.

One of the lead authors on the study, Andrew Oberst, recently gave an interview about how it worked, how it might be improved, and his research team’s plan for the future.

How the Immunotherapy Study Works

Oberst said the first step in the study was to create tumors in the mice. They did this by injecting lung tumor cells or melanoma cells into the mice. Then they also introduced dying cancer cells of those same two types. When the dying cells were introduced, Oberst says that the immune system activated and began to attack the tumor. This led to the tumors becoming smaller and longer survival times for the mice.

Oberst went on to say that tumors were also reduced when dying cells of a different type were put into the mice. He identified this as the most surprising part of the study. It is the most surprising because the different cells did not have any of the same antigens that are in the tumor, so the immune system was just responding to a hostile environment. Typically, it only responds to calls from specific cancer fighting cells.

Study Design

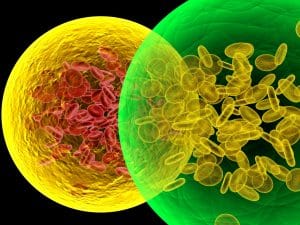

When speaking on the study design, Oberst said that the goal was to study the immune response to necroptotic cells. So they took dying tumor cells and injected them into the live tumors to see if the immune system would be drawn there. They found that this activated a celsuicide inducing enzyme called RIPK3. The researchers then wanted to find a way to activate RIPK3 in live tumors without the dying cells. So they put a key gene from the dying cells into the live tumors, and this also caused the immune system to fight the tumor.

Study Limitations

In discussing the limits of their study, Oberst said that the way they created the tumors in the mice makes the cancer easier to cure than a typical one. While the result is still positive, it remains to be seen if the approach will be as effective when the tumor is not created this way, and when the tumor is in a human. This means that more studies are needed.

What’s Next?

And Oberst says that this is where his team are headed next. They want to work on more “physiologically relevant” tumor models and see if they can replicate the results they saw in the mice. He also said that some of how the cells work together, and how the suicide inducing enzyme works on the tumor, is still slightly unclear. A foray into this area could lead to better immunotherapy treatments and a wider variety of options for patients facing all kinds of cancer.